Tomorrow’s prospective medical students may have many more options for where and how to obtain a medical degree – including the possibility of designing one’s own medical educational program. The launch of the AAMC’s Global Health Learning Opportunities (GHLO) program last week will help to build a framework around international clinical electives – but GHLO may also contribute to some very different thinking about gaining a degree in medicine. “Program” may need to replace “School” or “Institution” as students increasingly seek opportunities to be educated and trained in different parts of the world to enrich their clinical experience, and/or gain benefits from lower tuition fees or a shorter time to graduation than that in the United States. This was just one of the many issues highlighted at the Globalization of Medical Education Session held at the 2012 AAMC Annual Meeting on November 4th, which was introduced by Dr. Robert Crone, CEO of Strategy Implemented and Dr. Janette Samaan, Director of the AAMC GHLO program.

Tomorrow’s prospective medical students may have many more options for where and how to obtain a medical degree – including the possibility of designing one’s own medical educational program. The launch of the AAMC’s Global Health Learning Opportunities (GHLO) program last week will help to build a framework around international clinical electives – but GHLO may also contribute to some very different thinking about gaining a degree in medicine. “Program” may need to replace “School” or “Institution” as students increasingly seek opportunities to be educated and trained in different parts of the world to enrich their clinical experience, and/or gain benefits from lower tuition fees or a shorter time to graduation than that in the United States. This was just one of the many issues highlighted at the Globalization of Medical Education Session held at the 2012 AAMC Annual Meeting on November 4th, which was introduced by Dr. Robert Crone, CEO of Strategy Implemented and Dr. Janette Samaan, Director of the AAMC GHLO program.

The Session aimed to show academic medical institutes an alternative picture of the possible new globalized marketplace in which we will be operating. One where fewer students and trainees would be coming to the US for their degrees and certification, and where academic programs outside North America will be increasingly attractive to US medical students as well. Session speakers had many different perspectives on globalization, which were masterfully teased out by the moderator, Dr. Lewis First, Professor and Chair of Pediatrics, Vermont University College of Medicine and Chair of the National Board of Examiners.

Leaders of 3 prominent international medical schools with American roots, namely American University of Beirut, Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar and Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School, emphasized that it is already possible to deliver education internationally, of equivalent high quality to that in the US. Indeed lessons learned from Duke-NUS program are now being transferred back to Duke University in North Carolina. All the schools described their programs and the success of their students who are working throughout the world.

As medical education and postgraduate training diversifies and globalizes, so too will evidence-based accreditation of programs and assessment and certification of students and trainees. Dr. Thomas Nasca, CEO of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Dr. Donald Melnick, CEO of the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) both envisioned major change in the accreditation landscape. Dr. Nasca advocated for greater integration and coordination of education program accreditation and of individual performance certification, than currently exists in the US. Dr. Melnick went so far as to suggest that “named” medical schools may no longer be considered an adequate proxy for a quality education as competency-based assessment becomes more granular and continuous throughout education, training and finally throughout a physician’s career of practice. Dr. Emmanuel Cassimatis, CEO of the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) outlined new programs and products that ECFMG is developing to address the need for the portability of primary-source verified documents throughout a physicians career, regardless of where they are practicing in the world, as well as the need to ensure that medical schools and programs do undergo rigorous accreditation based on WFME standards. The importance of accreditation was seconded by Dr. Dan Hunt, Co-secretary of the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME), which is, upon request, providing consultation services to regional and national accrediting bodies and medical schools around the world.

As medical education and postgraduate training diversifies and globalizes, so too will evidence-based accreditation of programs and assessment and certification of students and trainees. Dr. Thomas Nasca, CEO of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Dr. Donald Melnick, CEO of the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) both envisioned major change in the accreditation landscape. Dr. Nasca advocated for greater integration and coordination of education program accreditation and of individual performance certification, than currently exists in the US. Dr. Melnick went so far as to suggest that “named” medical schools may no longer be considered an adequate proxy for a quality education as competency-based assessment becomes more granular and continuous throughout education, training and finally throughout a physician’s career of practice. Dr. Emmanuel Cassimatis, CEO of the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) outlined new programs and products that ECFMG is developing to address the need for the portability of primary-source verified documents throughout a physicians career, regardless of where they are practicing in the world, as well as the need to ensure that medical schools and programs do undergo rigorous accreditation based on WFME standards. The importance of accreditation was seconded by Dr. Dan Hunt, Co-secretary of the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME), which is, upon request, providing consultation services to regional and national accrediting bodies and medical schools around the world.

Dr. Lois Nora, CEO of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) emphasized the importance of specialty certification not only as a point in time, but also continuously through maintenance of certification strategies as ABMS extends its footprint outside of the United States. Dr. Nora was enthusiastic and optimistic that the US organizations that make up the US “House of Medicine” can work together and with their international counterparts to “change the world” by enhancing quality of training, raising standards of care which will lead to improved outcomes for patients world-wide. There is mentioned benefit of learning from institutions abroad as well.

A lively discussion with the speaker panel concluded the Session – below is a summary of some additional questions addressed by the speakers and questions and comments that were received about the topic via email, text and twitter. The presentation is available on the AAMC 2012 website. In the meantime, we look forward to seeing any comments and questions you might have! — The SI Team

Questions on the Role of the US:

Q1. How do we reconcile the reputation of US medical training as the best in the world with the fact that our health care system is nowhere near the best in the world? Shouldn’t the best education system lead to the best health outcomes?

A1. Arguably the best education system should lead to the best health care outcomes for patients treated by graduates of that education system. At the same time, the education system is only one component of a country’s health care system. Health outcomes are likely dependent upon many additional factors such as equitable access to health care, public health and safety environment, equitable socioeconomic conditions, etc.

Q2. How are US centric accrediting and assessment organizations working with international institutions to help them create their own sustainable in-country systems rather than relying on US agencies for the long term?

A2. In countries with small populations of medical professionals (independent of socioeconomic status) there is a long history of collaborating with external or international groups to support medical education, training and assessment incountry. As a result of the many initiatives underway by US, Canadian and European entities it is anticipated that broad-based international associations may be created for healthcare professionals of which any national entity could become a part – in much the same way as the airline industry created IATA to ensure standardization for the safety of its passengers, crew and aircraft.

Questions to Medical Schools Using US Curriculum Internationally:

Q1. What cultural challenges to regional healthcare education and research collaborations exist for your school(s)? And how are/can they be successfully addressed?

A1. While globalizing best practice in medicine should enable all citizens of the world to have access to equivalent high quality care, there is no question that localization and cultural understanding and sensitivity are critical to success.

Q2. Do American accreditation guidelines and requirements for healthcare education fully meet the health care needs of local populations?

A2. The majority of human health concerns are common, globally, and so broadly speaking where US guidelines and requirements for medical education and assessment have a proven track record of serving those common concerns, they work for other non-US populations. However, there are always local demographic, cultural and systems differences and these need to be reflected in curricula development and in the design of examinations.

Q3. Are any/all of the schools wanting LCME accreditation? Are you accredited by an international accrediting organization? If so, which one?

A3. WCMC-Q being a branch campus of the WCMC in NY, seeks such recognition by LCME. While WCMC-Q is recognized by ECFMG on the iMed database, and is part of various international listings, an International accrediting organization does not currently accredit it.

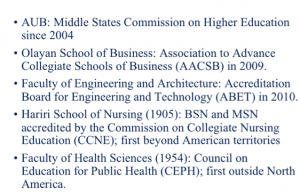

It is safe to say that all schools want a US-standard accreditation modeled after the LCME. Like WCMC-Q, AUB is not accredited by an international accrediting organization. The University and several of its Faculties, however, are accredited by top US organizations (see Dr. Kamal Badr’s PowerPoint below).

Q4. What percentage of grads from AUB, Qatar and Singapore end up practicing in these countries, as opposed to coming and staying in the US?

A4. WCMC-Q is a young school, having graduated only 112 doctors in the last four years. Most of them are still finishing their residency/fellowship training in the US and elsewhere. While WCMCQ fully expects a substantial percentage of graduates to return to Qatar, it is too early to make any realistic projections at present.

According to Dr. Kamal Badr, 40% of all Lebanese physicians graduating every year end up practicing in the United States. The figures for AUB are closer to ninety percent.

Q5. How has the change of model changed the cost of providing education? Is it less? If so, do you charge less in tuition to reduce student debt?

A5. WCMCQ’s tuition and related fees are equivalent to WCMC in NY. Qatar Foundation provides interest free loans to mitigate the burden of carrying student loans.

Dr. Kamal Badr said if anything, the “change of model”, which he assumes means the new curricula and assessment standards, is more costly. AUB’s tuition fees have been rising steadily, but so have AUB’s financial support packages and loans. No AUB student is refused admission or promotion for financial reasons.

Q6. Please discuss issues with obtaining US residency spots and overcoming the barriers.

A6. This is a major issue for Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (WCMC-Q) graduates and for other IMGs. The broad category of IMGs encompasses a wide variety of institutions all over the world and their quality can vary tremendously. It is not surprising that there are negative stereotypes surrounding IMGs. Dean Sheikh believes that the single best way to overcome this barrier is to consistently and repeatedly be able to place WCMC-Q graduates at very good residency programs. This will establish a track record, which should make it easier for future generations of WCMC-Q graduates.

As for AUB, Dr. Kamal Badr said AUB’s ultimate goal is for AUB graduates to complete their residencies and fellowships at AUB. Historically, AUB residents have gone on to complete fellowship training in the US because AUB residency qualified them to sit for the Boards. With the new regulatory environment in US medical training, the refusal of ACGME to accredit programs outside the US and its territories has resulted in all students finding residency slots in US institutions. AUB graduates have faced no barriers in finding US residencies. The hope, however, is that the new direction taken by the US organizations to transpose their standards abroad, exemplified by the ACGME-I and likely soon by ABMS-I, will create pathways for graduates of accredited programs to go on to fellowship training in the USA if they wish to do so.

Questions to LCME:

Q1. There are educational programs that are developed/being developed to train US citizens with a global perspective and to return to practice medicine in the US. What is the position of the LCME with regards to accrediting these programs?

A1. LCME is responsible for the accreditation of medical education programs leading to the medical degree in the United States and Canada. At the present time, there are no plans to extend accreditation beyond the passport granting territories, provinces, and states of these two countries. The LCME has been active in providing assistance to other regions or countries in developing their own medical education accreditation systems. This is consistent with the approach of the World Federation of Medical Education (WFME) who encourage regional accreditation bodies who can be sensitive to local health care needs and local customs and practices. In order to assure a minimum level of quality of these accreditation systems, the WFME provides a process for recognition of these regional accreditation systems.

Q2. What does the LCME think of US schools partnering with non-US schools which have Accreditation – not through LCME – but through their own country’s accreditors?

A2. The LCME has no position on schools outside of the US or Canada that partner with LCME accredited medical schools.

Q3. Will the LCME consider accrediting global programs that are truly university based and allow students to study as part of their degree abroad?

A3. At the present time, the LCME is not entertaining a future of accrediting medical education programs outside of the US and Canada.

Questions on Support for Developing World:

Q1. There were many questions associated with the impact of globalization in regions where there is social and economic disparity, for example:

- If an international assessment program were agreed upon, how might that be paid for – especially in resource poor regions?

- Considering that about 100 medical schools with graduate programs will be opening in Africa in the next 10 years, are you prepared to take any steps to help them adequately develop and prepare their programs?

- How do we ensure that quality rises faster than cost?

- The international accreditation/certification initiatives will have the effect of fostering migration from the south to the north. Do we have an ethical responsibility to prevent the potential devastation to the medical systems of the LMICs?

- What is the relationship between country or regionally based accreditation standards and healthcare graduates’ desires to move and practice globally especially in underserved areas?

A1. Many issues emerge when trying to solve inequalities in healthcare and education in different regions of the world. Probably, among the most critical for sustainability are:

- Stable Government

- Healthy economy

- Adequate financing systems for healthcare and education

- Public health and safety environment

- Employment and personal growth opportunities in healthcare and education

- K through 12 education systems

- An indigenous desire to become a healthcare professional in the region

- High quality graduate training in good clinical facilities that leads to job opportunities in country

If technology, networking and professional collaborations make education and training models more portable, affordable and have real local value, then accessibility to medical education and training becomes less dependent on where you live. The hope would be that this also contributes to better access to higher quality healthcare for citizens around the world. All the US entities currently developing or operating international programs share this vision.

Questions about Products and Services:

Q1. What is the relationship between eFolio and EPIC?

A1. EPIC has been designed by the ECFMG as a repository of primary source-verified credentials for individual International Medical Graduates that can also serve the needs of regulatory bodies worldwide. It is expected that EPIC will evolve further in response to IMG needs.

For more information see http://www.ecfmgepic.org/

The AAMC and NBME are developing eFolio in response to the need to drive inter-operability of data contained in an increasing number of disparate portfolio systems. The aim is to create a meaningful data set for medical students, residents or practicing physicians.

For more information see https://www.aamc.org/download/76810/data/efolio.pdf

and http://www.nbme.org/research/CIprojects.html

Q2. Advise if “international foundation of medicine” benchmark exam is good enough to prove meeting with US medical standards.

A2. The IFOM exam addresses content determined by an international panel of experts to be relevant to the knowledge and skills of a medical student receiving a medical degree anywhere in the world. The IFOM is intended to determine an examinee’s relative areas of strength and weakness in general areas of clinical or fundamental science, not to predict performance on USMLE. The content covered by the two examinations is somewhat different. However, because there is substantial overlap in content coverage and many IFOM items were previously used in USMLE, it is possible to roughly project IFOM performance onto the USMLE score scales. The results of IFOM would not be considered equivalent for purposes of obtaining a license to practice medicine in the US or certification from the ECFMG. It may be considered a measure of the requisite knowledge and skills to pursue educational activities in the US that do not require a medical license or completion of USMLE components.

For more information about IFOM see www.nbme.org/ifom2013.